Press

-

No Depression – Elana James: Making a New Name for Herself

March 11th, 2007 at 7:28pmMarch-April 2007

By Rich Kienzle

Austin, Texas – “I don’t think that many people knew me as Elana Fremerman to begin with. James is so much easier to remember,” says the former fiddler and vocalist for Hot Club Of Cowtown. “It’s from my middle name [Jamie]. It’s easier to spell. It’s been excruciating over the years, to have people make such an effort to remember.”

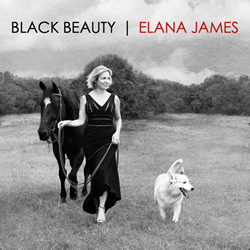

Changing her professional name wasn’t James’ only transition these past couple years. After the Austin trio disbanded in 2004, she pondered remaining in music, going back to school, or even returning to her onetime summer occupation of horse wrangling.Living in Austin, she’d met Willie Nelson and earned the respect and friendship of Texas Playboy fiddler/mandolinist extraordinaire Johnny Gimble and his family. Meeting Gimble, whose work with Willie and others made him iconic in his own right, had a particularly special meaning for her.

“When I moved here in 1998 … I’d hardly been to Texas but I knew Johnny Gimble lived in Dripping Springs, which is outside of town. It’s been incredible to get to see him,” she says. “I don’t get to see him enough. I was at his party for his 80th birthday. I always learn from just being around him – the jokes he tells and everything he talks about, things that involve other fascinating people. He’s just full of stories, and they’re never about Johnny, they’re always about somebody else and what somebody else did. He’s of the old school of genteel geniuses who are, thank God, still around.”

Deciding on her professional future became easier last year when legendary Nashville producer Fred Foster, overseeing an album teaming Willie with Ray Price and Merle Haggard, invited her to play twin fiddles with Gimble on the album. That followed another high-profile experience in early 2005, when she spent several weeks on the road with Bob Dylan as a member of his backing band. Later that year, she formed a new trio. Elana James & the Continental Two. And now she has just released her self-titled solo debut, which blends originals with classic western swing, country and jazz.

A Kansas native – her father was an ad executive, her mother a violinist with the Kansas City Symphony – James began studying classical violin at age 5, and later became a highly competent equestrian. “I only listened to things like ‘80s pop when I was growing up and took up classical music,” she says. After high school, she moved through varied academic studies, both nonmusical (Eastern religions) and musical (classical and Indian). Still, she always felt constrained by classical music’s intrinsic lack of spontaneity.

Working summers as a wrangler on a Colorado ranch and playing fiddle in the ranch’s cowboy band proved a respite from the rigid structure of the classics. During another stay in New York, she gravitated to western swing. She met guitarist Whit Smith, and the two began jamming in Manhattan bars. Eventually that led to a move to San Diego, where she and Smith formed the original Hot Club. They scuffled there for a time, then moved to Austin in 1998, recording five albums before the band dissolved in 2004.

Hot Club may be history, yet for James, the past remains her focal point. “The gravitational center of the way I think about … music almost exclusively has to do with old-timers, people who are now old-timers,” she explains. “Those are the people who are current to me even if they’re not alive, like Johnny Gimble and Wade Ray and Buck Owens. I’m not emptily trying to prop up the past. There just really aren’t fiddle players that I’m focused on that are alive today. I just listen to recordings and I’m so utterly … knocked off my feet.”

Some of her favorite albums include Merle Haggard’s 1970 A Tribute To The Best Damn Fiddle Player In The World (the record that launched the Bob Wills revival) and reissues featuring Hugh and Karl Farr (the jazz guitar/fiddle duo within the early Sonss of the Pioneers) and vocalist Jack Guthrie (Woody’s cousin) with Billy Hughes’ scintillating swing fiddle. Sometimes things get misplaced. “The truly great stuff. I have to buy it again every two to three years,” she laughs.

Is Dylan, known to have a musicologist’s command of older music manifested in the obscure tunes he sometimes performs onstage, a swing fan? In this case, her answer is a bit cagey. “I think you’d have to ask him. That’s really not something I could answer.”

She’s more animated remembering of legendary 1930s virtuoso Stuff Smith and Danish swingmaster Svend Asmussen than the mannered, delicate style of the better-known Stephanie Grappelli. Along with the fiddle instrumental “Silver Bells” and the Bob Wills favorite “Goodbye Liza Jane” is her sublime take on Dylan’s “One More Night.” “Not a lot of people have done it,” she says of the Dylan tune. “I don’t really know who’s covered it, but it’s not that commonly done and it’s just a beautiful song.”

James based her sweet rendition of “The Little Green Valley,” written and recorded in 1928 by Carson Robison, on a 1957 version by another overlooked western swing fiddle and vocal giant: Wade Ray, who led his own band and later played with Ray Price’s Cherokee Cowboys, Willie and Ernest Tubb. It came her way during the 2006 Dylan tour.

“I loved all that stuff he did on that Cherokee Cowboys [solo] album,” she says of Ray. “On ‘Little Green Valley,’ I love double harmony and I love [his] harmony singing. Donnie Herron, on the tour with Dylan, we were flying and passing CDs back and forth across the aisle. He said, ‘Yeah, man, I got the entire Wade Ray collection.’ I used to have that and over the years, I don’t know what happened to it. So while we were flying from one show to the next I burned all of his Wade Ray songs onto my computer.”

While her jazz vocal phrasing evolved over the past few Hot Club albums, James seems to have found her comfort zone singing Duke Ellington’s “I Got It Bad (And That Ain’t Good)” and “I Don’t Mind.” “The people I have the biggest affinity for are people like [1930s jazz vocal giant] Mildred Bailey or these kinds of unadorned vocalists who have this elegant, simple delivery,” she says. “It’s deceptively simple, actually, because it’s effortless and understated and tasteful and warm, but it’s rich and emotional.”

“The singer I do like to go see when I’m around is [veteran jazz cabaret vocalist] Blossom Dearie in New York. I’ve seen her several times at Danny’s Skylite Lounge where she plays. I love her singing. That is a style I’m attracted to, but of course who doesn’t love Billie Holiday? Enough people are going down that path and that’s not naturally what I’m about.”

The original compositions had some interesting inspirations. She wrote “Down This Line,” its instrumental intro inspired by Luther Perkins’ now-legendary guitar solo on Johnny cash’s “Folsum Prison Blues,” after seeing the Cash biopic Walk the Line. “I hope I made that different enough,” she reflects. “I harmonized it in kind of a weird way. What was so neat about [Cash’s] whole story, there were many things, but one was that he stuck with the original band forever. That was such a moving component, and the simplicity of those solos was so fresh and makes you realize that less is more.”

Another original, “All The World And I,” creates a more reflective, almost hypnotic mood. “I tend to also like songs that are almost modal. That’s a song where I indulged that,” she says. “There’s a kind of a meditative, restful quality. You don’t want to do it all the time, but every so often, it’s like a tonic.”

She ponders the challenges posed by both a repertoire heavy with non-originals and her preference for sharing the spotlight onstage. “If you are an artist and you’re billed under your own name,” she observes, “nowadays a person goes to see you and they generally expect you to have written most of the songs you are performing, and you are the chief interpreter of everything.

“But I’ve especially noticed fiddle combos, from Stuff Smith to Bob Wills or whatever, sort of pass the torch around the band. So much of playing fiddle is comping behind a vocalist. I mean, why would I want to sing every song when half the fun is just playing the song, and who cares who sings it? I hope that’s not going to be a problem when we tour this year.”

Though James still takes the majority of the vocal leads in her shows, she doesn’t consider that to be a requirement. “I do sing most of the songs, but Bob Wills hardly sang,” she points out. “He just went up there and brought the charisma level up into the stratosphere, which is all he needed to do. Someone who’s a name, it’s mostly going to be them-them-them-them-them. But I love a band, and I like to play music with people.”

Featured Item

VISIT GIFT SHOP

Elana James

"A beautiful voice, a fantastic musician, with the heart and soul of an angel."

-Willie Nelson